Knowing how brief cases is essential to success in law school, particularly for new students. In this post, we’ll discuss:

The Key Ingredients

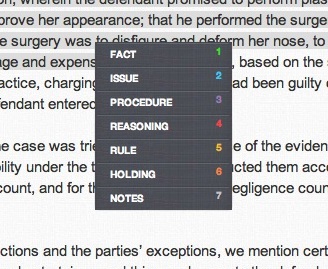

Most case briefs can be broken down into six elements:

- Facts – the basic who, what, where, and when of any case. Facts are useful to understanding the eventual holding and reasoning of a case, and fully participating in lecture. While law school exams rarely require students to regurgitate facts, knowing the details of cases can help students spot issues, analogize to precedent, and effectively apply law to unfamiliar fact patterns.

- Procedure – the procedure (or, more formally, procedural posture) can be thought of as the legal history of a case. The procedure is the section of a case that recites how the case came before the court of record. The procedure often will include references to the court that the case began in, past rulings in the litigation, the ultimate result of past litigation, and which issues were appealed. Much like the basic facts of a case, knowing the procedural posture of cases aids class participation and effective application of rules of law during exams.

- Issue – this is the legal question that the court attempts to answer in its decision. Often prefaced with phrases such as “the issue before us…” or “in this case we are examining whether…,” correctly recognizing the legal issues in a case is essential to determining what the eventual rule and holding of a case is. Though students sometimes think of legal issues in a fact specific context – whether the contract between Bob and Jane in this case is valid – it’s more useful to boil them down to their legal elements, i.e., whether an oral contact for the sale of goods valued at more than $500 is enforceable under the laws of State X.

- Rule – this is the statement of law that governs the decision reached by the court in a given case. The rule(s) used in a case often appear after introductory phrases such as, “the rule is…,” “statutes in State X state…,” or “the relevant precedent in our circuit is…” Unlike a holding, a rule is broadly applicable, and not just specific to the case at issue. Students who aren’t certain if they’ve correctly identified a rule in a case should ask themselves whether the proposed rule would be applicable to another case with different facts. This will help to distinguish between rule statements that are too fact specific – “Bob and Jane’s oral contract for the sale of $600 of house paint is unenforceable in State X” – and those that are correct statements of law – “the statute of frauds in State X requires contracts for the sale of goods valued at more than $500 be in writing to be enforceable.” The rule is perhaps the most essential element of a case brief, as it is how students learn the individual principles of law in a given subject area.

- Reasoning – the reasoning is the portion of the case where the court applies its previously stated rules or public policy to the facts at hand. The reasoning can be thought of as the “why” of the case – why the court arrived at its eventual holding. Correctly recognizing the reasoning of a court opinion both prepares students for lecture as well as helps students learn how to apply rules to fact patterns during exams.

- Holding – the holding is similar to the rule in a case, but is much more specific to the case at hand. Holdings can be brief statements, such as “affirmed,” or “reversed and remanded,” or fully fleshed out sentences such as, “we hold that the contract between Bob and Jane is unenforceable under the statute of frauds in State X and remand the case to the district court for further proceedings.”

How to Brief a Case the Old-fashioned Way

Before LearnLeo, law students had three choices when it came to briefing cases. Though each method had its advantages, they both came with significant trade-offs. Now, with LearnLeo, students are able to combine the advantages of both methods of case briefing without the significant trade-offs of either.

Stand-alone Case Briefs. In this method, students would read a case and largely transcribe the facts, procedure, issue, rule, reasoning, and holding into their notes, either by hand or on a digital note program. Students who briefed in this fashion would have a solid collection of notes from which to construct an outline, but would often find that their reading and class preparation took considerably longer than students who engaged in book briefing. Almost every law student starts off creating stand-alone case briefs, however, because of the length of time it takes to create these case briefs for each case assigned in law school, the vast majority of students switch to book briefing by their second term.

Book Briefs. Students using this procedure create their briefs directly in their casebooks by highlighting or underlining case elements (in different colors if they are particularly diligent) and scribbling notes in the margins. This method is often faster than transcribing the notes to a separate program, but the gains in speed are offset by an inability to alter the content of a brief after it is created (a problem that can be significant for students just learning the basics of case briefing) and a dependency on having a casebook at all times. In addition, students cannot organize the materials in a book brief – they are stuck with the organization of the case and can be forced to scramble to find important materials when called upon in class. Students who rely on book briefing also find it more difficult and time consuming to create outlines at the end of the semester as much of their notes will be “trapped” in their book.

Commercial Briefs. While commercial briefs can be useful in a pinch, it is often counterproductive to use them in lieu of briefing or even reading cases. Students typically use commercial briefs because they don’t have time to brief themselves, but they come at a significant cost to learning since the process of identifying the important elements of a case is essential to understanding a case. Moreover, being able to quickly identify the relevant portions of a case is a crucial skill for practicing attorneys – a skill that is gained by practice.

How to Brief a Case the LearnLeo Way

LearnLeo brings together the best of both the stand-alone case briefing method and the book briefing method. With LearnLeo, students can intuitively highlight and take notes (keeping the learning process intact) on digital copies of the cases assigned by their professors online. With a single click, the student’s highlights and notes can be pulled from the case into an organized stand-alone case brief. Should the student feel the need to correct their original brief because of items learned in lecture, they can easily remove, add or modify highlighting and notes, automatically updating their case briefs. Visit our step-by-step tutorial for details on briefing cases the LearnLeo way.

LearnLeo gives students the speed of book briefing without the need for lugging around heavy casebooks or difficulties in creating outlines at the end of the semester. And if a student loses the briefs they have previously downloaded due to computer failure, all of their notes and briefs are securely backed up on LearnLeo servers in the cloud. All a student needs to access and restore all of their notes is an internet connection.